The FOOD OF WAR collective was formed by Omar Castañeda and Hernán Barros, two Colombian artists based in London and Andreina Fuentes, a Venezuelan artist based in Miami.

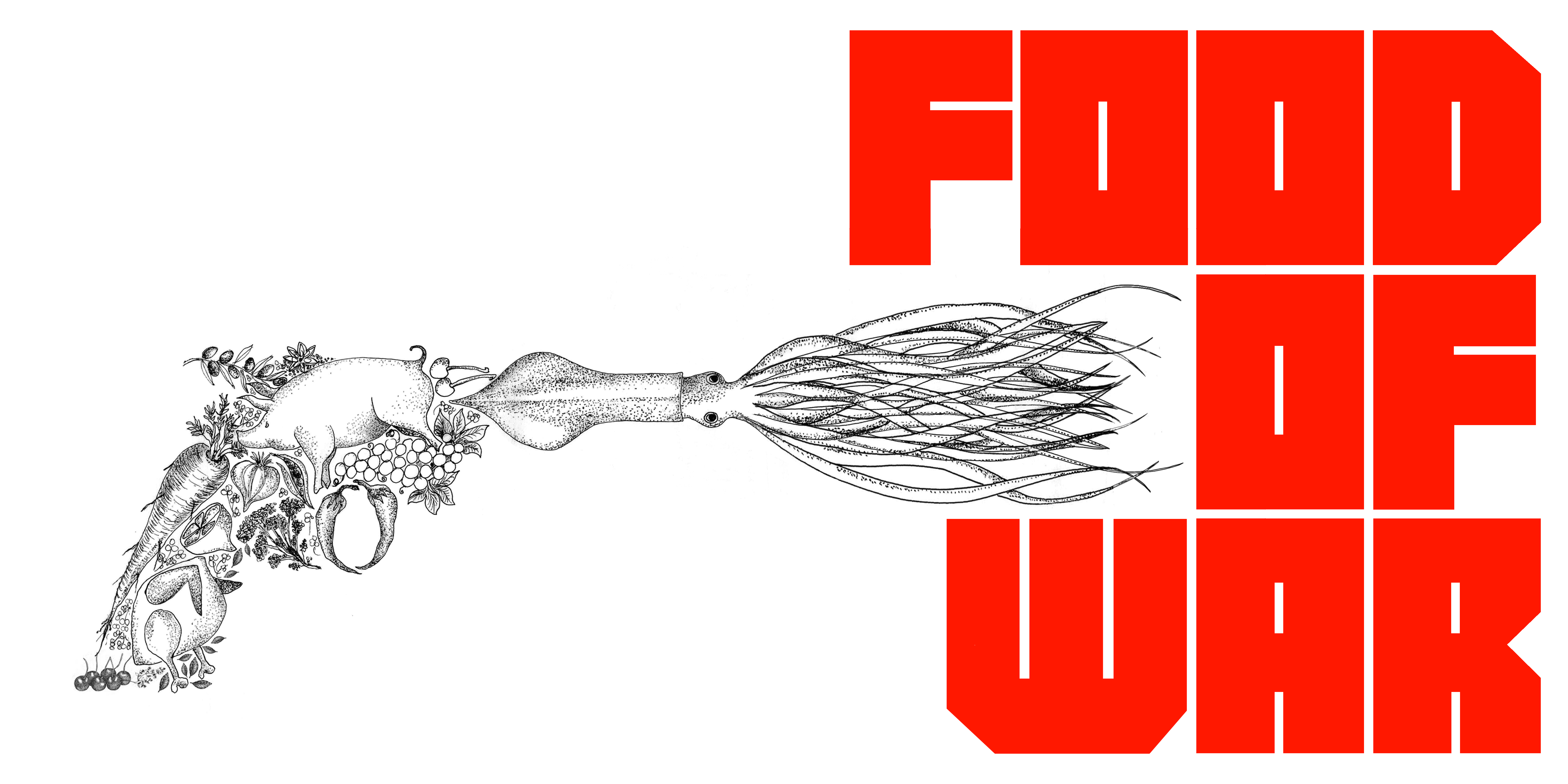

FOOD OF WAR is a multidisciplinary art collective dedicated to explore the relationship between food and conflict through any artistic expression. Their proposals involve performative interactions with the public, involving food, bringing reflections on the issues we face in relation to our alimentation, its production, distribution, local and global, among other issues that they explore from their artistic practice.

To get closer to the work that FOOD OF WAR does, we share with you this interview conducted for airWG with its founding members and guests, where they tell us about their work experience in the residency as well as their interests and ways of operating from a multidisciplinary artistic practice, always open to dialogue and collective work.

When and how did your interest in art begin? Why did you decide to start a collective like Food of War and how do you link it to your individual practice?

Accessing art was a powerful experience for both of us. It’s hard to pinpoint when exactly this interest started, but we consider that it was akin to learning how to speak and express ourselves. The limitations of language forced us to find new ways to communicate, and art was exactly this. It gave us a voice, in a place where individuals like us are often cast aside and discriminated against. Art nurtured and accompanied us, it fed us.

Food of War was a result of a powerful realization. On a trip to Israel, we became aware of the so-called “Hummus Wars” between Israel and Lebanon. A conflict that went beyond that of trademark and authenticity, it was yet another hidden expression of war. We realized that food accompanied conflict in all its levels. Scarcity and abundance are the most general markers of this, but delving deeper, we Understood that Food of War was a sort of memento. A cultural force that is profound and frank. Present in the most unlikely places. Ready to feed you the most terrible realities. Once you see it you can’t unsee it. And so, Food of War as a collective became our way to pass this on, to share a plate.

What is the personal connection between conflict and food for Omar Castaneda?

Growing up in Colombia, a country known as the host of the longest-running contemporary conflict, was an experience that I try to explain through my artistic practice. Growing up, it’s almost as if I was being force-fed violence, terror, kidnapping, and corruption. You couldn’t escape it. And that’s why I guess I’m somewhat obsessed with it now.

For Hernan Barros, founding member of FOW, and Andreina Fuentes, active artist in the collective, what is your personal approach to the central theme of Food of War?

Hernán Barros: Like Omar, the experience of conflict is intrinsic to my experience as a Colombian individual. Yet, I need to translate this to meaningful artistic experiences, and so I consider my relation to the theme to be that of an experimental artist. I find food to be such an interesting alternative medium, and so, although it can be a powerful subject, I also feel inclined to use it as style, as material. Our projects always have a gastronomical element to them. I believe in engaging the senses, to immerse our audiences in our own world.

Andreina Fuentes: from my artistic practice with the FOW collective, I am interested in relational work to apply exhibition-action methodologies and sensitive pedagogies in programs that involve art and social action in community contexts, stimulating collective participation, targeting issues such as food shortages, malnutrition, and food education.

FOW incorporates artists from different practices, including gastronomes, cooks, and producers, as well as situations specific to the context where the proposals are developed. How is the work dynamic between you, how do you problematize and propose strategies for research, production, collective/individual execution?

We’re far away from establishing a final process or methodology for our projects. Not sure if that’s good or bad (perhaps the latter), but we’re slowly realizing what the best approach to each of our artistic experiences is. We’ve lately been introducing a model of research-production that seems to be quite efficient, yet it’s always accompanied by a highly experimental way of working. Our brainstorming sessions don’t only happen at the beginning. They’re there to guide us throughout the project like necessary palate cleansers for our obsessive work periods.

Certainty arrives and then disappears. That’s why our collaborators and artists have our full trust and respect. Because many times they’re the ones who push a project to the finish line. In that sense, we’re trying to work in a way where we build creative teams and then let them do their magic. In one of our most recent initiatives, edible murals, that’s exactly what we’re doing. Seeing as it’s a travelling project, we assemble teams specific to the mural’s location and context, and give them the resources to create, produce and engage.

We don’t know how much continuity this will have, we’re a collective that expands and contracts, and right now we’re expanding, but who knows, perhaps we’ll go back to our guerilla style initiatives, depends on how hungry we are.

Concerning this, could you tell us about your research in Amsterdam, your experience during the residency at airWG, what tensions did the dynamics of the city, the community and the Dutch culture present and how was this reflected in the production and execution of your proposal?

Amsterdam was great. Variety is a word that comes to mind. The menu has something for everyone, especially art lovers. What we quickly realized is how established the commercial gallery scene is, and although we think this is incredible and important for the livelihood of artists, it’s not really what we wanted to bring to the table.

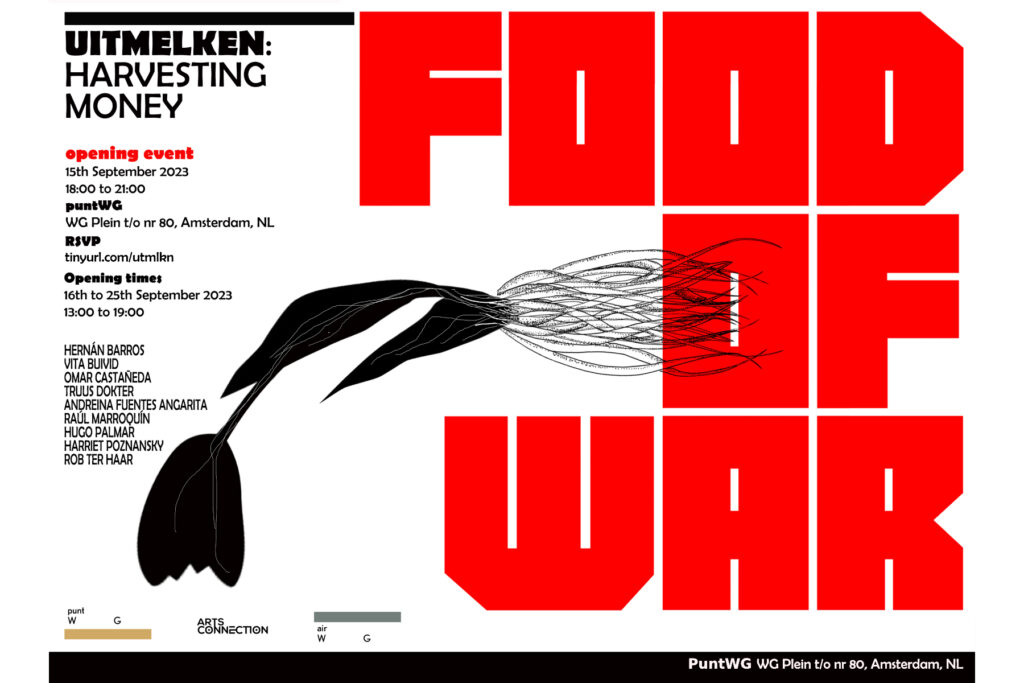

We were keener on establishing dialogue on themes that are either not well-known or simply uncomfortable to bring up. It was apparent that these themes were of interest, and little by little our collaborations started ensuing. We were welcomed by the Dutch public, and this translated in all our collaborators supporting us in good will and creating their own smaller projects within UITMELKEN: Harvesting Money. We’re generally quite unaware of tension, we don’t register it much. We generally ask and we get.

Why UITMELKEN: Harvesting Money and why the artists and other guests who were part of the collective during the final show? How does the collective manage the tension between the production of projects, installations, and the issue of sustainability?

Why is always a strange question. It simply felt right. It felt like the type of collective exhibition that Amsterdam needed at that point in time. It’s almost like we hosted a party and all the artists and guests started arriving. We exhibited both artists we knew and artists we met during the residency, so there wasn’t a set agenda or planned lineup.

The 80% of artwork exhibited was recycled or repurposed for this exhibition (some of the paintings date back to the 80s!) most of our installation materials are rented, so they produce no waste, and there’s a high volume of digital work which is quite less resource consuming. These are small feats trying to work towards a more sustainable practice, yet we’re still learning.

Food, identity, territory, war, ideology, religion, production, village, inequality, technology, gastronomy, taste, food, conflict are words that surround the central theme of FOW: What about the possible effect of art in going beyond conflict, what have been their experiences from the artistic practice and what are the searches that currently feed the present of FOW with a perspective to the future?

Art has always introduced itself in conflict. It has given its victims hope and a way to transcend the objectivity conflict tends to transmit itself with to the public. Protest almost always uses some sort of creative outlet to produce emotion to the masses, and it’s undeniable that art plays a role in transmitting reality, whatever that reality is. Art has been used to mobilize and to liberate. It’s also been used to oppress.

We don’t consider it can go beyond conflict, but it’s imperative to record it, and in our idealistic minds, to pick up its remnants, and make them into something meaningful.

UITMELKEN: Harvesting Money, Installation FOW at puntWG Amsterdam. Photos by Ilya Rabinovich.